Bonnard, Attention, and Free Will (553 words)

- Rainey Knudson

- Feb 5, 2024

- 3 min read

I would have missed Bonnard's Worlds at the Kimbell if my old friend, the writer Christina Rees, had not texted me that it was the best thing she'd seen in years.

I would not have appreciated this show when I was young. I would have seen these paintings, seen the dates Pierre Bonnard was working, and swiveled dismissively right out of the galleries. I remember him vaguely from school as just a lesser Impressionist. But he's a full generation later, born just two years before his friend Henri Matisse.

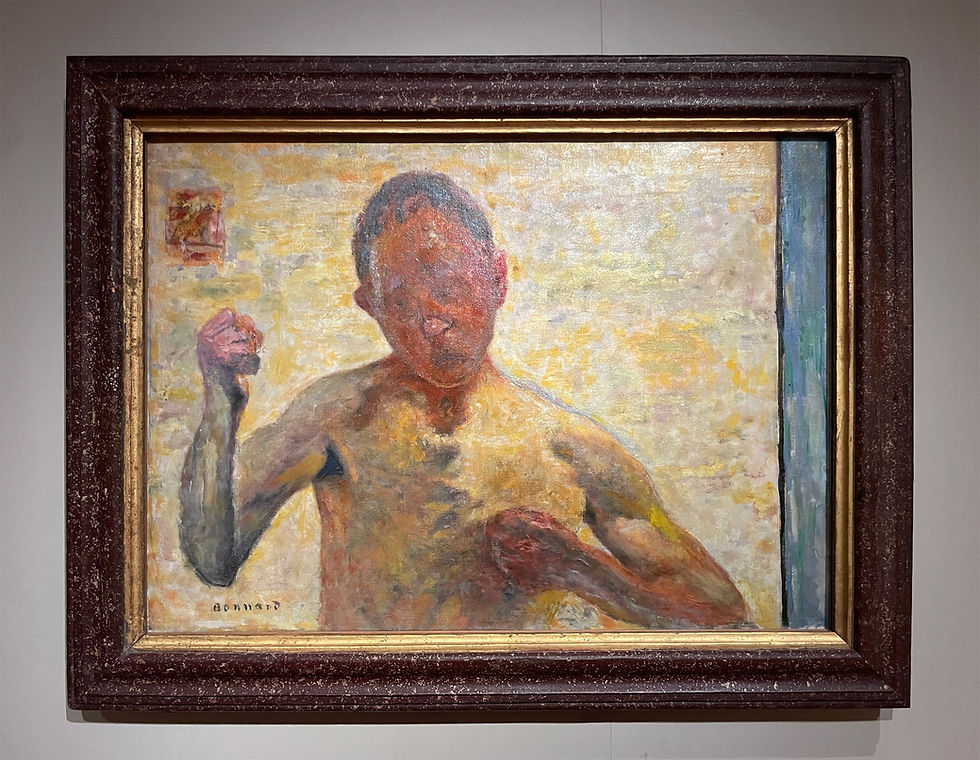

This guy is painting during World War One, during the grim bacchanalia and the hardship of the interwar years, during World War Two. And he did stuff like this.

This is not art for people who view contentment as something for the addle-headed or the lazy. This is not the work of the wild, badass geniuses (the only kind of genius worth being, right?) whom one associates with the early 20th century. Where is the showy experimentation of Picasso? The irony of Duchamp? The harrowing brutality of Soutine? The everything-is-broken wackadoodlery of the Dada and Surrealists? Those are his contemporaries. What is Bonnard up to, painting these cheerfully odd studies of his everyday life when the world has gone to hell?

Bonnard was not clueless: he had to decamp with his family to southern France during the Nazi occupation. He knew what was going on. But he doesn't appear to have wallowed in the current events of his time, at least not in his art. He was simply attentive to what was immediately around him: his wife, their beloved animals, his house, his larger family, the natural world. Ultimately, himself.

Bonnard was attentive—humorously, weirdly, gloriously attentive, to seemingly prosaic things. Did he at some point quit reading the news so much? Did he try to tune out the distressing chatter, the horror show of the terrible wars, the frightening despots, whole countries gripped by madness? Did he try to slow his mind down, to see, closely and attentively, the actual, real life that was there in front of him? I wonder: of all the legendary artists working at that time, is this the guy who is showing us best how to live? Or is he merely (as my younger self would have said) sticking his head in the sand?

The show, which is now en route to the Phillips Collection, is brilliantly organized as a sort of long, slow, cinematic zoom shot. It begins with wide-angle landscape vistas, continues through views of gardens from within houses, then observations of moments in those houses' rooms, then deeper, to his wife Marthe de Méligny's bed and bathroom and loving studies of her body made over the years, and finally, to the artist himself looking into a mirror, in a haunting trio of self-portraits that were painted over a span of 30 years. There is no chronology, so different paintings of the same subject made decades apart are all hung together.

The cumulative effect is a series of breadcrumbs that lead us to an interior life, a different sort of hero's journey than Bonnard might have made getting wrapped up in the events of his time and spewing them out angrily in his art. The show reminds us that we are free to attend to whatever we wish.

All photos are from my phone, and of course do not do justice to the works. Go see them in person if you can.